Ripples of Gratitude: The Flow-on Effects of Practicing Gratitude in the Classroom Environment

Jane Wilson, Westmont College and Paige Harris, Westmont College

Abstract

This research explores God’s call to gratitude, summarizes current research on the benefits of gratitude, identifies key gratitude disciplines/practices, and utilizes a conceptual framework to study gratitude in the context of educational settings. In contribution to the relatively recent discussion on gratitude, especially in the education field, the researchers explored the effects when pre-service teachers practice an inner attitude of gratitude and intentionally express gratitude in the classroom setting. This study expands the current educational research of gratitude by incorporating three primary gratitude practices – the State of Preparedness, gratitude language, and gratitude journaling – and examining both personal benefits and flow-on effect toward the teaching-learning process. Fourteen pre-service elementary school teachers were invited to practice gratitude during nine weeks of their full-time fieldwork placements. Participants experienced personal benefits such as enhanced well-being, strengthened relationships, and heightened cognitive skills. Ripples of gratitude were observed as positive flow-on effects in their classrooms: a more positive and calmer classroom atmosphere, better behaved students, and students more willing to focus effort towards learning. Pre-service teachers also experienced a flow-on effect towards themselves through increased resiliency when facing adversity and greater satisfaction in teaching. These findings are significant for the field of education as the power of gratitude can foster positive transformation through promoting engaged environments and strengthened relationships for both teacher and student.

Introduction

“Wake up, be alert, be open to surprise. Give thanks and praise — then we will discover the fullness of life, or rather — the great-fullness of life.” Brother David Steindl-Rast, interfaith scholar (in Emmons, 2007, p. 119)

Even though gratitude has been identified as a central virtue in most religions, and is discussed in the fields of sociology, ethics, moral philosophy, and politics, only recently has gratitude been studied scientifically. In the past 15 years, social science researchers have delved into the power of gratitude, identifying its definition and meaning, the benefits it produces, and the practice of cultivating gratitude. As people experience the personal benefits of gratitude, they notice something similar to a ripple effect. “Gratitude broadens people’s modes of thinking, which in turn builds their enduring personal and social resources. Gratitude appears to have the capacity to transform individuals, organizations, and communities for better” (Fredrickson, 2004, p. 159).

The current research has primarily focused on the psychological, spiritual, and physical benefits of gratitude with only limited research on the cognitive benefits of practicing gratitude. Understanding cognitive benefits has important implications for educators. The purpose of this study is to explore the ripple or flow-on effect on the teaching-learning process when teachers practice gratitude. Specifically, the researchers invited 14 pre-service elementary teachers to engage in three primary gratitude practices during their fulltime fieldwork placements. After choosing to practice gratitude, the participants identified personal benefits experienced, as well as the ripple effect upon the students in their classroom.

This research explores God’s call to gratitude, summarizes current research on the benefits of gratitude, identifies key gratitude disciplines/practices, and examines a conceptual framework for studying gratitude in the context of educational settings. The present research study is then described as well as its significance for the field of teacher education. The hope is that this study can broaden and build upon the discussion of how gratitude enhances the teaching-learning process.

Background

God’s Call to Gratitude

Gratitude is a central theme among virtues; this wisdom has been passed along from ancient philosophers and theologians across all religions. As long as people have lived they have sought ways to express gratitude to God, the ultimate giver. The great religions teach that gratitude is a hallmark of spiritual maturity. Indeed, God’s call to express gratitude is strong and clear. To be thankful is seen as a command, a natural response, and a challenge when facing trials and adversity.

The Bible directs our attention to gratitude as a prominent theme; thankfulness is mentioned 150 times, and 33 times as a command to be thankful in all circumstances. “Be joyful always; pray continually; give thanks in all circumstances, for this is God’s will for you in Christ Jesus” (I Thess. 5:16-18). Though God directs His people to be thankful, it often emerges in believers as a natural response when they learn of God’s generous grace and goodness, which is unexpected and undeserved. Swiss theologian Karl Barth explains, “Grace and gratitude go together like heaven and earth: grace evokes gratitude like the voice and echo” (as cited in Emmons, 2007, p. 90). The Old Testament reminds the readers numerous times to express gratitude for God’s loving-kindness, “Give thanks to the Lord for He is good; His love endures forever” (I Chr. 16:34, Ps. 106:1, Ps. 107:1, Ps. 118: 1, 29, Ps. 136:1). While expressing gratitude for God’s goodness appears to be a natural response, God challenges His people to remain grateful even amidst difficult circumstances. In the New Testament, Peter gives reason to be thankful for trials and suffering as “they may result in praise and glory and honor at the revelation of Jesus Christ” (I Pet. 1:6-7).

Current Gratitude Research

Though gratitude has been exalted as a common virtue for centuries among theologians and philosophers, it has only been studied scientifically over the past 15 years. In the relatively young field of positive psychology, gratitude has emerged as one of 24 character strengths that help people lead meaningful and flourishing lives (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Gratitude as a character strength refers to appreciation for the benefits we receive from others and the desire to reciprocate with our own positive actions. Those who possess this character strength have a deep awareness and acknowledgement of goodness in their lives.

This growing body of groundbreaking research on gratitude points to several beneficial effects. The research demonstrates that gratitude enhances people’s lives psychologically, spiritually, physically, and cognitively (Emmons, 2007; see also summary of research at Greater Good Science Center). The evidence that cultivating a spirit of gratitude promotes the well-being of people is substantial. Spiritually, grateful people experience greater connectedness with God and more peace and contentment. Psychologically, grateful people experience more positive emotions, lower levels of stress, and healthier relationships. Physically, grateful people experience more energy, healthier hearts, better sleep, and increased longevity. Cognitively, grateful people are more alert, focused, creative in problem solving, and appreciative of learning. Dr. Robert Emmons (2014), a leading expert in the scientific study of gratitude, recently summed up the bulk of gratitude research at the Gratitude Summit, “Gratitude has the power to heal, energize, and transform lives.”

Intentional cultivation of gratitude. Researchers explored whether gratitude is a genetic disposition or a learned trait. Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, and Schkade (2005) argue that 50% of one’s tendency towards happiness or gratitude is one’s genetic set-point, 10% is related to one’s circumstances, and 40% is connected to intentional activity. With this given information, psychologists have identified a group of intentional activities, disciplines, and/or practices that can be used to strengthen one’s level of happiness or gratitude. If people view gratitude as something that can be practiced, they can train themselves to focus their minds on gratitude-inducing experiences and then label them as such.

Gratitude as a spiritual discipline. For Christians, gratitude is a hallmark of spiritual maturity, and they express thanks to God in their prayers, worship, and sermons. Thirteenth-century German theologian Meister Eckhart suggests, “If the only prayer you say in your life is ‘thank you’ it would be enough” (as cited in Emmons, 2007, p. 90). For individuals, gratitude can be expressed through daily prayers of thanks for blessings received and for the strength to face challenges. Another practice is to breathe scripture by silently mediating on a section of scripture as one inhales, and silently exhaling a silent thank you. Gratitude can also be experienced through communal expressions of thanks. That is, when people corporately testify to God’s goodness, the whole faith community becomes a circle of thanksgiving to God (Miller, 1994).

Henri Nouwen (1994/2013) views gratitude as a spiritual discipline involving intentional choice, “Gratitude can also be lived as a discipline. The discipline of gratitude is the explicit effort to acknowledge that all I am and have is given to me as a gift of love, a gift to be celebrated with joy.” Nouwen clarifies how he chooses gratitude, instead of complaint, even when he feels hurt, resentful, or bitter. Gratitude as a spiritual discipline also involves action. Johannes A. Gaertner explains, “To speak gratitude is courteous and pleasant, to enact gratitude is generous and noble, but to live gratitude is to touch Heaven” (as cited in Emmons, 2007, p. 90). Christians who fill their heart with gratitude feel a natural desire to express their thanks in words or actions to God and others.

Gratitude as a practice. Froh, Miller, and Snyder (2007) argue that gratitude does not come naturally; rather it is a learned process and sometimes an effortful one, requiring a certain level of introspection and reflection. Similarly, Watkins, Uhder, and Pichinevskiy (2014) found that participants who daily recounted blessings were training their brain with cognitive habits which amplify the good in their lives. Gratitude must be practiced and cultivated. A number of gratitude practices have emerged in the recent literature. All of these practices invite people to stop and notice blessings, savor those blessings, speak of those blessings, and respond (see Greater Good Science Center, focus: gratitude).

Gratitude journal. To engage in this gratitude practice, people identify and record three to five specific blessings either on a daily or weekly basis. This practice tends to be more effective when participants focus on gratitude towards people over material objects, take time to savor each blessing, and remain open to surprises in their life.

Gratitude letter. In this gratitude practice, people think of an individual in their life whom they have never properly thanked and then write a letter (approximately 300 words) that expresses specific thanks to such person. Research suggests that writing, delivering, and receiving gratitude letters can enhance joy for both the author and the receiver (Emmons, 2007; see Greater Good Science Center, focus: gratitude).

Gratitude conversation. People can experience the benefits of gratitude when they engage in conversation with others about positive events, experiences, or outcomes that happen each day. This can occur at the dinner table by asking each member to say three good things about the day. Time can be taken to savor these blessings.

State of Preparedness. This gratitude practice, developed by Kerry Howells (2012) at the University of Tasmania in Australia, invites students to examine their inner attitude and reflect forward to a class or to the day ahead, reflecting honestly on their personal outlook. The State of Preparedness practice asks students to determine if they hold an attitude of gratitude or resentment and then encourages them to consciously choose a grateful perspective.

Gratitude in Education

A growing number of academics, educators, and community leaders suggest that gratitude is one of seven character strengths (gratitude, grit, zest, self-control, optimism, social intelligence, and curiosity) that are predictive of student success in academic settings (Tough, 2011). Yet currently only one book exists that focuses specifically on gratitude in education (Howells, 2012). In this book, Howells presents gratitude as a pedagogy that underlies effective instruction and argues that when students thank when they think, they think in more engaged ways.

Howells (2012) begins with the premise that students want to be engaged learners, but do not know how to do so. In her university courses, Howells guides her students to examine the positive impact of a grateful attitude by contrasting it with an attitude of complaint or resentment. When students enter class with a spirit of complaint, this limits their ability to think, concentrate, integrate information, or see value in learning. In contrast, when students enter class with an inner attitude of gratitude, they are more engaged, focused, and motivated to exert effort towards learning. Howells encourages her students to take charge of their own attitudes by utilizing a minute at the beginning of class to be aware of their attitude and mindfully choose a grateful spirit. She coined this gratitude practice, “A State of Preparedness” (Howells, 2012).

Howells (2012) points to the importance of teacher modeling of gratitude as a central entry point for tapping into its transformative power to enhance learning. Indeed, before students can be expected to practice gratitude, teachers must model gratitude. Virtues such as gratitude are caught, not taught. In a small qualitative pilot study, Howells and Cumming (2012) reported outcomes identified by six pre-service teachers when they intentionally applied gratitude in their fieldwork placements for four weeks: improved relationships, enhanced wellbeing, and improved teaching outcomes. Pelser (2013) replicated their study and found similar results with an addition of social support outcomes when he studied six pre-service teachers across a two-week period. An additional outcome from these studies is a conceptual framework for considering gratitude in the context of pre-service teachers’ professional experience.

Conceptual Framework

Howells and Cumming (2012) present a conceptual framework as they approached their research with pre-service teachers. They advocate the notion of gratitude that involves a dynamic interchange of giving and receiving a gift. This framework encourages participants to consider what gratitude means to them personally, and guides participants to discuss the challenges of practicing gratitude in the context of the school environment. The framework includes the following assumptions:

- Acquisition of gratitude is a step-by-step process, not mastered instantly.

- There may be situations where it is impossible or inappropriate to practice gratitude.

- Participants are invited (not required) to practice gratitude.

- Gratitude should not be used to manipulate others.

With this framework in mind, Howells offers a definition of gratitude in the field of education, yet encourages participants to add their own meaning.

Gratitude is the active and conscious practice of giving thanks. It finds its true expression in the way one lives one’s life rather than as a thought or an emotion. It is an inner attitude that is best understood as the opposite of resentment or complaint. Gratitude is usually expressed towards someone or something. (Howells, 2007, p. 12)

Research Study

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this qualitative study is to explore the impact on the teaching-learning process when pre-service teachers engage in gratitude practices for nine weeks. This study builds upon and extends the work of Howells and Cummings (2012) and Pelser (2013) in two ways: increased sample size and length of study, and the identification of the flow-on effects of gratitude towards the teaching-learning experience. The previous studies examined six pre-service teachers each for two-four weeks, whereas this study examines the experience of 14 pre-service teachers for nine weeks. The previous studies focused on the personal benefits of gratitude, whereas this study examines both the personal benefits as well as the ripple or flow-on effects of gratitude onto the teaching-learning process.

Participants

Each of the 14 participants in this study was enrolled in a year-long Multiple Subject Teaching Credential Program at a small Liberal Arts Christian College. During the fall semester, these pre-service teachers took five education courses; during the spring semester they engaged in full-time fieldwork placements in local elementary schools and attended a weekly seminar. These 14 pre-service teachers were invited to examine and implement gratitude practices during their full-time fieldwork placements in the spring semester of 2014. The participants were all female, ages 21-23.

These pre-service teachers taught kindergarten through sixth grade in five different elementary schools. Eight of the pre-service teachers taught in schools in which 50-60% of students received subsidized school lunch, 40-55% had limited proficiency in English, and 80% identified themselves as Hispanic, 16% White, and 4% other. Six of the pre-service teachers taught in schools in which 30% received subsidized school lunch, 25% had limited proficiency in English, and 60% identified themselves as White, 34% Hispanic, and 6% other.

Two researchers collaborated together to familiarize themselves with the literature and design and conduct the present study. They met weekly to discuss insights and make plans for how to discuss gratitude in the following seminar. One researcher served as the supervisor to the pre-service teachers, so she chose to maintain a low profile during seminar discussions on gratitude. The other researcher was one of the pre-service teachers, which provided an insider perspective and a key informant. Since it was essential that the pre-service teachers should not feel coerced or required to practice gratitude, the pre-service teacher researcher led all of the discussions about gratitude during the seminar, including the initial overview of the study and the invitation to practice gratitude.

Data Collection

Prior to beginning their 2014 spring full-time fieldwork placements, the pre-service teachers gathered for a day-long seminar to discuss elements of a successful fieldwork experience. Towards the end of the day, the pre-service teacher researcher set the tone for this research study by summarizing and highlighting the possible benefits of practicing gratitude: transformed individuals, enriched personal health, strengthened ability to deal with adversity, deepened relationships, heightened cognitive thinking, and improved classroom atmosphere (Emmons & McCullough, 2004; Howells, 2012; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). By describing possible benefits of gratitude, the researchers hoped this information would motivate the pre-service teachers to consistently engage in gratitude practices. After describing the benefits and the key gratitude practices, the pre-service teachers were invited to engage in gratitude practices and seek to notice the impact. They were reminded that practicing gratitude was not a requirement; it was their choice to engage in the gratitude practices. Guided by the conceptual framework from Howells and Cumming (2012), the pre-service teachers were then cautioned that they might not feel grateful at all times, there might be situations where it feels impossible or even inappropriate to be grateful, they should not expect gratitude in return, and they should not use gratitude to manipulate students.

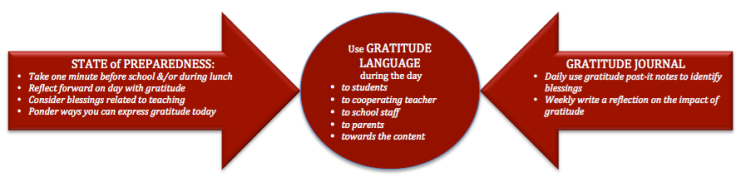

Three primary gratitude practices were described and encouraged: State of Preparedness, gratitude language, and gratitude journaling (see Figure A). During the weekly seminar, the pre-service teacher researcher led discussions about gratitude and its impact in the teaching setting. After nine weeks of incorporating gratitude practices, the pre-service teachers completed a final assessment which asked them to self-identify how often they engaged in the primary gratitude practices, the effects of these practices, and the challenges they experienced when implementing these practices.

Figure A: Gratitude Practices

Gratitude Practices and Discussion

This section defines the gratitude practices utilized in this study and includes specific insights from the pre-service teachers. Selected comments represent a collective perspective and an effort was made to include at least three comments from all fourteen participants. All names have been changed to protect confidentiality. Following each comment is a code to indicate the medium in which the comment was presented (GJ = gratitude journal, SM = seminar, TW = tweet, FA = final assessment, IM = individual meeting). Following the code is a number that indicates the week the comment was made.

The pre-service teachers reflected upon their experience of practicing gratitude both generally and specifically. Generally, the pre-service teachers expressed the need to be intentional in practicing gratitude. For example, Harper wrote, “Gratitude is something that needs to be intentionally practiced. I feel more connected and more in the present when I practice gratitude” (GJ6). Beka also expressed the need for intentionality, “I learned to make conscious decisions to feel thankful, which gave me optimism, energy and calmness” (FA9). “The practices create a good discipline,” Colleen explained, “I think the brain needs to be trained to think in a certain way, so I am developing a habit of being thankful” (GJ8).

All of the pre-service teachers expressed that they experienced general positive benefits by practicing gratitude. Helene tweeted, “I was surprised that the internal effect of intentional gratitude was so noticeable” (TW9). During seminar Harper communicated, “Gratitude has been empowering as a professional and helps make everything I do more meaningful” (SM4). “These practices,” Gayle wrote, “continue to bring me joy throughout the day and allow me to stop and recognize the simple things that make my day brighter. By practicing gratitude, it helps me avoid a complaining attitude in myself and… not lose sight of daily teaching delights” (GJ8).

Three key gratitude practices were utilized in this study: State of Preparedness, gratitude language, and gratitude journaling. Each practice is defined, including how often the pre-service teachers self-identified engaging in the practice. Comments made by the pre-service teachers are included to describe their personal experience of engaging in the particular practice.

State of Preparedness

The gratitude practice “A State of Preparedness” as coined by Howells (2012) was emphasized as the primary practice to cultivate an inner attitude of gratitude. To engage in “A State of Preparedness” pre-service teachers were urged to take one minute each morning before they got out of their car in the school parking lot to reflect forward on the day. They were encouraged to be mindful of blessings they would encounter throughout the day as they interacted with students, teachers, and school staff, to reflect honestly on the outlook they would bring to various situations, and to ponder ways they might express gratitude during the day.

The pre-service teachers self-identified engaging in the State of Preparedness approximately four days each week. They expressed that the State of Preparedness helped them focus and center their minds as they prepared for the day ahead. Gabby wrote, “When I take the extra minute before heading into school, I feel that it helps me set the tone for the day… I am more grateful for the day because I have thought about what a privilege it is to be teaching. I was surprised how quickly it could change my mood and my state of mind for the better” (GJ9). “When I get to school,” Nancy explained, “I take a minute to be grateful. The result of doing this every day has been substantially positive… It really helped my day be much brighter” (GJ3). Sage tweeted, “I’m surprised that the State of Preparedness refocused my mind and heart to enter the day calmly and intentionally” (TW9). Pris reported during seminar, “The State of Preparedness helps me put other stuff behind me and focus on teaching” (SM4).

These pre-service teachers were all professed Christians and many modified the State of Preparedness practice to align with their Christian faith. Colleen noticed the natural alignment in her first week of doing the State of Preparedness, “I did the preparation exercise in my car when I arrived at school. It felt just like praying and allowed me to center myself. I recognize how gratitude flows seamlessly with praying and how much gratitude is naturally in my prayers. It’s helpful for me to put the two together in my life and see the connection” (GJ1). Corey used her moment in the car to, “ask God for patience in my thoughts, words, and actions” (SM3). Helene often referenced her faith in relationship to the State of Preparedness practice, “Taking a moment to get ready for the day helps me to gather the Lord’s strength to love on those kids and teach them with His strength. It reminds me of the bigger picture. Some days I thanked God for specific students. It was a great way to start my morning, to put my day into perspective, and it reminded me that there are so many things to be thankful for in every student” (excerpts from GJ1,6,8). Crissa prayed during her State of Preparedness, “I spend a couple of minutes praying for my students for my State of Preparedness. These practices helped me stay more positive. When I recognize the value of each student, it reminds me that no matter how I feel in any moment, I want to do what will benefit the student” (GJ2).

During seminar, some of the pre-service teachers admitted that they felt rushed in the morning and would forget to do the State of Preparedness in their car. They then suggested and implemented utilizing one minute midday, often during lunch, to refocus their hearts and minds for the afternoon. Doing the State of Preparedness practice at midday helped to calm their hearts. Gayle particularly liked doing the State of Preparedness at midday, “It helps me most when I do the State of Preparedness midday, and especially on Fridays. These are times when I was feeling exhausted, and the State of Preparedness changed my perspective… it helped me to refocus and appreciate the joys of teaching in the middle of the day” (GJ5). “Doing a midday State of Preparedness,” Beka wrote, “has really helped me focus for the rest of the day and be thankful for this opportunity and the students that I teach. It really helped focus my thoughts and heart” (GJ5). After hearing from her colleagues, Harper felt inspired to try a midday State of Preparedness and reflected, “It provides a boost of energy that sustains me for the rest of the afternoon” (GJ7).

Gratitude Language

The pre-service teachers were encouraged to use intentional language during their fieldwork placement that expressed gratitude towards their cooperating teacher, their students, the school staff, and the principal. In addition, they were urged to speak with appreciative words towards the content they were teaching. Finally, the pre-service teachers were counseled to write gratitude notes with specific words of thanks and praise to each student during their placement. The pre-service teachers self-identified that they daily expressed gratitude either orally or in written gratitude notes.

“Gratitude language,” Stacy explained to her colleagues, “is a practice where I narrate and express thanks for the students’ behavior, thinking, or work” (SM5). Crissa challenged herself with a specific strategy, “My goal is to remember the 5-1 ratio, giving 5 expressions of gratitude for every one correction” (GJ4). Colleen explained, “By practicing gratitude, I am reminded to stand strong and speak only words that affirm my colleagues and students” (GJ6). Many pre-service teachers grew in their ability to speak or write using specific words of affirmation. For example, Mandy wrote, “I’m trying to be very specific when I express gratitude to my students, because I can tell it means so much more — at least that’s true for me (GJ3).

All of the pre-service teachers wrote gratitude notes to their students and expressed specific words of thanks. Helene was surprised with the positive impact of the notes, “I sent home a few gratitude notes and my students were beaming… I had no idea this would be such a big deal” (GJ2). “Students responded gratefully for the notes of encouragement I put in their desks,” Gabby wrote, “I can see them smile as they read them. Then they seem more attentive, happy, and focused” (GJ3). Writing these notes also appeared to boost the spirits of the pre-service teachers. Gayle explained, “I found that writing my gratitude notes really helped me refocus and appreciate the joys of teaching” (GJ3).

Gratitude Journaling

Gratitude journaling was also offered as a practice to consider. In their weekly written reflections, pre-service teachers were required to identify insights into teaching and set goals for the upcoming week. In addition, they were given the option to reflect on gratitude practices and describe its effect on the teaching-learning process. Though not required, the pre-service teachers averaged writing about gratitude seven times during the nine week research project. If the reader carefully examines the comments inserted within this article, one will notice most of the evidence comes from written comments in the pre-service teacher’s weekly journal.

Many pre-service teachers wrote about the ways in which writing about gratitude shifted their thinking. Harper wrote, “Journaling about gratitude and meditating on the gifts in my life has definitely transformed my inner attitude” (GJ5). “When I write about gratitude,” Pris explained, “I realize how much joy I experience throughout the week, and how much it overpowers the tough moments” (GJ5). Colleen concurred, “My mind automatically wants to flashback to frustrations of the week, but writing about gratitude redirects my mind to present joy” (GJ8). Gabby shared a similar comment, “When I reflect on the week with a grateful heart and write about it, this allows me to see the hard moments as opportunities for growth instead of bumps in the road” (GJ9). Corey commented about the power of gratitude journaling, “This helped me develop a habit of thinking of things I was grateful for each day” (SM2).

Data Analysis

The grounded theory method of qualitative analysis (sometimes referred to as constant comparative method) was used to analyze the data (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Grounded theory seeks to illuminate a phenomenon that is grounded in the data. A systematic set of procedures is used to generate and build a theory that is faithful to the data. Creativity, rigor, persistence, and theoretical sensitivity all work together to create both artistic and scientific analytical balance. Essential to this analysis is continually asking questions of the data and then subsequently comparing answers with emerging ideas.

All data was carefully coded, analyzed, and triangulated: gratitude journals, seminar notes, individual meeting notes, tweets related to gratitude, and a final reflective assessment. The researchers wrote down and coded oral comments made by the pre-service teachers at the weekly seminar (SM) and during individual meetings (IM). Additionally, written data collected from the gratitude journal (GJ), tweets (TW) and final assessment (FA) was coded. Numbers were added to each code to indicate the week the comment was made or written. The researchers analyzed the data by literally printing out and cutting the data into separate comments, then restructuring the data by looking for emerging categories and then comparing each data point with the themes.

As categories began to emerge, the focus became to select common themes that represent the collective group of pre-service teachers. As a criterion for selecting collective ideas, an idea needed to be represented (in notes, journal, tweets, or final assessment) by at least 80% of the pre-service teachers. To further strengthen the data analysis, the pre-service teachers were invited to examine the emerging themes and concur or reject the veracity of the theme. This triangulation identified patterns and themes that ran throughout the data, identifying the collective perspective of practicing gratitude.

Results and Discussion

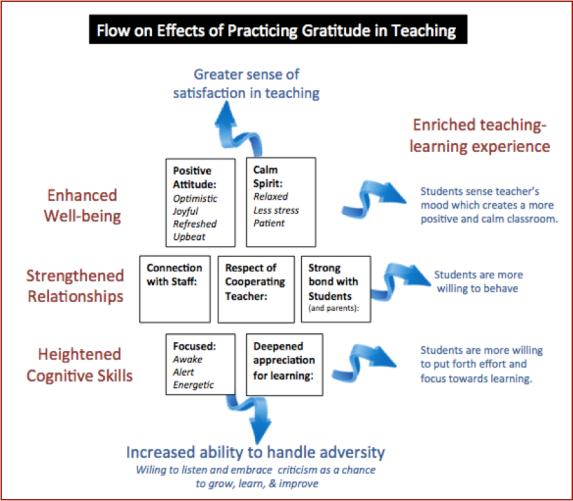

This section describes and discusses the themes that emerged from data analysis. By practicing gratitude the pre-service teachers experienced three personal benefits: enhanced well-being, strengthened relationships, and heightened cognitive skills. Most importantly, these personal benefits had flow-on effects that rippled out and enriched the teaching-learning experience for their students and themselves (see Chart A).

Chart A: Flow-on Effects of Practicing Gratitude in Teaching

Flow-on Effects to Teaching-Learning Process

As the pre-service teachers intentionally practiced gratitude, they noticed personal benefits that rippled out from themselves to others. In this section, initial comments identify the personal benefits they experienced. The following paragraph describes how these personal benefits rippled out and flowed on to their students in positive ways that enriched the classroom environment, aided classroom management, and enhanced learning.

Enhanced well-being: Ripples for the classroom environment. By practicing gratitude, the pre-service teachers experienced enhanced personal well-being by having a positive attitude and a calm spirit. They appeared to be more optimistic, joyful, refreshed and upbeat when they practiced gratitude. Mandy reflected upon the nine weeks of practicing gratitude, “Having a grateful heart can really affect your mood. My mood shifts from feeling down on myself to feeling happy and at ease when I choose to be grateful and in turn, the days seemed to be smoother (GJ9). “I have continued to be grateful in every situation,” Nancy wrote in her journal, “and I am finding myself happier and less tense. Being grateful really makes me feel like a happier, healthier, productive, positive person” (GJ5). “I was infused with joy and patience,” Harper explained, “willing to seek good in whatever the day brought” (FA9).

As the pre-service teachers experienced enhanced well-being by being more positive and calmer, they noticed a ripple effect. When they were positive and calm, their students appeared to be more positive and calm. “The students mimic the teacher’s mood,” Crissa wrote, “One day I was stressed and a little nervous and the kids in return were a little wild. The next day I was calm and the kids in turn were calm. Gratitude helps me to remain calm” (GJ6). Stacy reflected in her final assessment, “I found more joy in what I’m doing and a joyful teacher makes joyful students. If everyone is happy then the class runs smoother” (FA9). “I noticed that whatever attitude or emotion I was displaying,” explained Gayle, “caused my students to have those same emotions. I realized that I need to exemplify a grateful heart so my students can follow suit. This had a great impact on the class environment” (FA9). “When I am relaxed, calm and happy,” Corey observed, “then my students seem to be relaxed and happy” (GJ3).

Strengthened relationships: Ripples that aid classroom management. Practicing gratitude strengthened the pre-service teachers’ relationships in the school community with their cooperating teacher, students, the students’ parents, school staff, and principal. Fiona was feeling isolated at her school site, so she decided to be more intentional in expressing appreciation towards the staff, “This has allowed me to be welcomed into a whole new world of friendship, mentorship, and learning” (GJ9). Many communicated that when they expressed gratitude to their cooperating teacher, this raised their awareness of the exceptional support they were receiving which in turn helped them better support their students. While gratitude strengthened all relationships, it was particularly poignant for the relationships the pre-service teachers built with their students. “Gratitude has led to a personally deeper feeling of connectedness,” Fiona clarified, “Spending intentional time one-on-one with students allows me to appreciate them more and get to know them on a deeper lever. This deeper relationship strengthens their respect” (GJ9). Nancy concurred, “My relationships with my students and my cooperating teacher really blossomed when I expressed gratitude” (FA9).

When expressing gratitude specifically to students (orally or in gratitude notes), the pre-service teachers noticed that students were more receptive to their requests for appropriate behavior. This observation was particularly significant as classroom management is often challenging for pre-service educators. Sage reflected, “These gratitude practices reminded me to give priority to relationships. Students responded more promptly after we had built a strong relationship” (FA9). “If I’ve expressed gratitude by giving specific praise,” Stacy explained, “the students are more willing to cooperate with me” (FA9). Pris also noticed the power of being specific with praise, “Giving students a sticky note with specific praise…definitely makes a positive difference in that student’s behavior” (GJ5). Nancy tweeted, “Gratitude is a very beneficial element as a teacher. It helps with management, growth, and relationships. #whoknew” (TW9). “Often misbehaving students respond to my requests after I compliment them,” Beka commented, “It feels like a circle of gratitude” (IM6). Many of the participants noticed this circular effect of gratitude; their gratitude rippled onto the students and in turn, the ripples of response returned to them.

Heightened cognitive skills: Ripples that enhance learning. The pre-service teachers experienced heightened cognitive skills expressed as being more focused, alert, and energetic. Gratitude also deepened their appreciation for learning. Harper noticed this early on, “Gratitude awakened my personal learning for the day because I was thankful to be at school and learn all that I could from my cooperating teacher” (GJ1) and also after five weeks, “I’m more alert, excited, and joyful each morning (SM5). Colleen felt gratitude helped her engage her brain and manage her emotions, “I feel like an effective teacher because I can use my brain and not my emotions. Even when things feel frustrating, I can brush that feeling aside and feel grateful that I get to use my brain to solve another problem. I am modeling good thinking and problem solving skills to my students by doing this well” (GJ5).

When the pre-service teachers expressed gratitude towards the students and the content, they noticed a flow-on effect as their students appeared to be more attentive and willing to focus effort and attention on the content. Stacy wrote about the ripple effect, “My enthusiasm for the content rippled onto the students and they became excited to learn” (FA9). Gabby reflected, “Expressing gratitude to students really seemed to perk them up, getting them more invested and ready to learn” (FA9). “When I teach in a way that expresses excitement and gratitude for something,” Fiona explained, “this gets transferred to my students, and they become excited as well” (FA9). “When I verbalize the behavior I’m thankful for,” Sage wrote, “the student is more likely to participate, show effort, and stay on topic” (MA5). Helene summed it up, “Practicing gratitude has made me a better teacher. When I’m a better teacher, my students learn more” (FA9).

Flow-on Effects Towards Oneself

Two additional flow-on effects emerged towards the participants as individuals. As the pre-service teachers experienced enhanced well-being, strengthened relationships, and heightened cognitive skills they noticed flow-on effects toward how they handled adversity and their overall sense of satisfaction in teaching.

Increased ability to handle adversity. The pre-service teachers identified that practicing gratitude increased their ability to handle adversity. Since these pre-service teachers received a great deal of challenging feedback during their fieldwork (as do most pre-service teachers), this finding was particularly significant. Many benefits of gratitude strengthened this ability. Because practicing gratitude helped them to be more positive and calm, develop a respect for their cooperating teacher, and be appreciative of learning, they were more willing to listen and calmly embrace criticism from their cooperating teacher as a chance to grow and improve. “Gratitude changed my willingness to embrace difficult situations” Pris tweeted (TW9). Helene wrote, “I was surprised at the internal effect of intentional gratitude in me! Now I feel more grateful for challenges and see them as opportunities to learn” (GJ9). Sage expressed, “These practices help my mindset be receptive and calm when I get hard feedback. I’m grateful for the chance to learn and improve” (FA9). Mandy tweeted, “I was surprised to experience the change in my mood after choosing to be grateful for hard feedback” (TW 9). Fiona received an extra measure of challenging feedback, yet observed, “I am better able to respond to feedback and make changes if I am able to first appreciate the feedback I am receiving” (FA9). According to Beka, “Gratitude helps me breathe in ability to focus, process, and persevere when challenged” (TW9).

Enhanced satisfaction in teaching. The pre-service teachers expressed that practicing gratitude had a flow-on effect towards their overall experience as they experienced a greater sense of satisfaction in teaching. As their gratitude rippled out to their students and cooperating teacher, it appears that they in turn received ripples of blessings from their students and cooperating teachers. Nancy began this placement feeling discouraged, yet practicing gratitude positively impacted her, “I really found myself joyful and loving my job with being grateful in every experience” (FA9). “By practicing gratitude,” Beka wrote, “your job feels less like an obligation and more like a passion that you are fortunate to do” (FA9). “Gratitude has been so empowering,” Harper explained, “It makes everything I do more meaningful. By choosing to be grateful, I felt so energized and loved my teaching experience” (FA9).

Challenges and Possibilities

During the final reflective assessment, the pre-service teachers identified a few challenges to practicing gratitude: insufficient time, undeveloped habit, negativity, and insincerity. Though the pre-service teachers self-identified practicing gratitude approximately four days each week, they expressed that they often felt like they did not have time to do this. Indeed, the semester of full-time fieldwork placement is challenging and demanding. The pre-service teachers assume the equivalent of a full-time teaching position while also fulfilling personal obligations and additional requirements to earn their teaching credential. Some of the pre-service teachers explained that they had not yet developed a habit of practicing gratitude, so they would forget. Others expressed a spirit of negativity on their campus and in the staff room that prevented them from experiencing gratitude. And finally, some simply did not feel grateful, so trying to practice gratitude felt insincere to them.

There are some possibilities to consider that might counterbalance these challenges. Since the potential benefits of practicing gratitude appear to be significant to enhancing the teaching-learning experience, teacher education professors may want to help develop the habit of practicing gratitude in their methods courses. For example, education professors can begin class with a one minute “State of Preparedness” exercise, asking their students to reflect forward with a grateful heart on the class, being mindful of the opportunity to learn and to contribute to the discussion. Taking time to develop this habit during the methods courses could help establish a pattern for the pre-service teachers as they move into their fieldwork placement. Another possible strategy to consider is including gratitude journaling as a part of the methods courses. Perhaps, once each week the professor could devote five minutes to gratitude journaling, asking the students to reflect back on the week of methods courses and on their experiences in the field and then specifically identify blessings. As expressed by the pre-service teachers in this study, the gratitude journaling process shifted and transformed their thinking from focusing on negative experience towards positive dimensions of teaching. Moreover, if the professor can encourage students to be genuine and specific in their gratitude attributions, this might counterbalance feeling insincere at times.

Limitations and Future Research

Though this study builds upon and extends the work of Howells and Cumming (2012) and Pelser (2013), it is still limited by its small sample of 14 pre-service teachers. Additionally, this study is limited as it only worked with female pre-service teachers at the elementary school level. More studies are needed to explore the impact of cultivating gratitude on secondary pre-service teachers, male teachers, and credentialed teachers. A follow-up study could revisit these fourteen people to see if they continue to practice gratitude and what impact they notice as the credentialed teacher in charge. Additional research is needed to examine the student perspective when a teacher engages in gratitude practices. Moreover, studies could examine ways to cultivate gratitude in students and if by so doing, students would be encouraged to think in more alert and focused ways to enhance creative and flexible thinking in the classroom.

Significance

This study demonstrates that cultivating a grateful perspective in pre-service teachers positively impacted their fieldwork experiences. They experienced personal benefits such as enhanced well-being, strengthened relationships, and heightened cognitive skills. Ripples of gratitude were observed as positive flow-on effects in their classrooms: a more positive and calmer classroom atmosphere, better behaved students, and students more willing to focus effort towards learning. The ripples continued as they identified flow-on effects towards themselves as they reported increased resiliency when facing adversity and experienced greater satisfaction in teaching.

These findings are significant for the field of teacher education. If pre-service teachers complete their credential program with well-developed habits of gratitude and embody a grateful spirit in their first teaching position, they will hopefully experience similar benefits towards their personal well-being and towards an enriched teaching-learning experience for their students. Credential programs may want to consider engaging in gratitude practices during methods courses to help their credential candidates develop a habit of practicing gratitude. Specifically, professors can begin class with a one minute State of Preparedness exercise, model using intentional gratitude language, and provide structured time to write in a gratitude journal.

These findings are particularly intriguing for Christian teacher education programs as cultivating gratefulness aligns with God’s call to gratitude. This call to gratitude ripples out from professors who seek to model a grateful spirit and provide time in class to help students prepare their hearts and minds for class. With a grateful spirit, students may find themselves feeling more alert, focused, and appreciative of the opportunity to learn. For students who become teachers, their grateful spirit can ripple out and flow-on to their students to enrich the classroom environment. Gratitude, thus, not only strengthens one’s relationship with God, it also broadens and builds teachers’ ability to transform themselves and their classroom communities. Whether Christian teachers find themselves teaching in a Christian private school or a public school, they can honor God by modeling a grateful spirit and cultivating gratitude within their students.

References

Emmons, R. A. (2007). Thanks! How the new science of gratitude can make you happier. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Emmons, R. A. (2014, June). Why does gratitude matter? Paper presented at the Greater Good Gratitude Summit, Richmond, CA.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (Eds.). (2004). The psychology of gratitude. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (Eds.). (pp. 145-166).The psychology of gratitude. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Froh, J. J., Miller, D. N., & Snyder, S. F. (2007). Gratitude in children and adolescents: Development, assessment, and school-based intervention. In School Psychology Forum.

Greater Good Science Center. Retrieved from http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/gratitude

Howells, K. M. (2007). Practising gratitude to enhance teaching and learning. Education Connect, 1(8), 2-16.

Howells, K. (2012). Gratitude in education. Rotterdam: SensePublishers.

Howells, K., & Cumming, J. (2012). Exploring the role of gratitude in the professional experience of pre-service teachers. Teaching Education, 23(1), 71-88.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111.

Miller, P. D. (1994). They cried to the Lord: The form and theology of Biblical prayer. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press.

Nouwen, H. (1994/2013). Return of the prodigal son. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Pelser, J. N. (2013). Adventures in gratitude: Exploring the possibilities of gratitude in education. Unpublished thesis. University of Cambridge.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A classification and handbook. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA; Sage.

Tough, P. (2011). “What if the secret to success is failure? New York Times, 14.

Watkins, P. C., Uhder, J., & Pichinevskiy, S. (2014). Grateful recounting enhances subjective well-being: The importance of grateful processing. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1-8.